The History of RunMan

In celebration of its upcoming October 1st Steam release, the game's 15th anniversary and my 36th birthday, I present the incomplete history of the development of RunMan: Race Around the World. Please enjoy for a snapshot of the early days of indie games and GameMaker, game design theory from myself and @MaddyThorson, and a bit of history about the most legendary, beloved indie game you've never heard of.

Maddy and I started RunMan: Race Around the World when we were just teenagers. We were fans of each other's work in the budding Game Maker Community forums, and had prototyped some ideas together.

We worked on a previous unfinished platformer that was a Metroidvania... you were a blue blob character and you got all these movement upgrades, there was a lot of wallkicking. A lot of those ideas ended up in Maddy's excellent An Untitled Story.

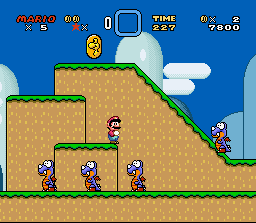

When we got back together we committed to doing a RunMan platformer. Maddy was a fan of the early arcade-style RunMan games and, like me, a big fan of Super Mario Bros. and Sonic. The potential for a full-length RunMan platformer was obvious.

I had been hesitant to take on a full RunMan game with different levels and worlds because I wasn't confident in my level design abilities. I had done a lot of arcade-style games that were short and constrained. Pairing up with Maddy to take the lead on level design was a dream come true.

Level design was Maddy's hallmark in games like Jumper, and from early on in her career, you could see she was just operating on a different plane with how she thought about and approached level design. No one in the Game Maker community (which comprised a large chunk of indie games in general at that point) was putting together levels so inventive, challenging, and fun.

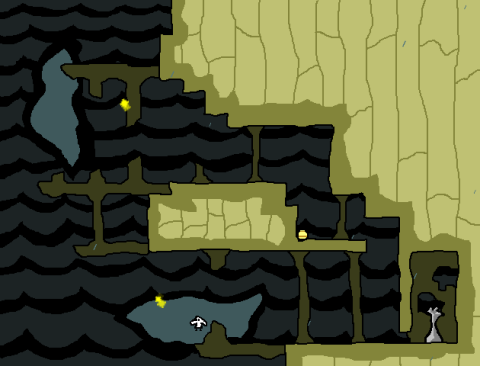

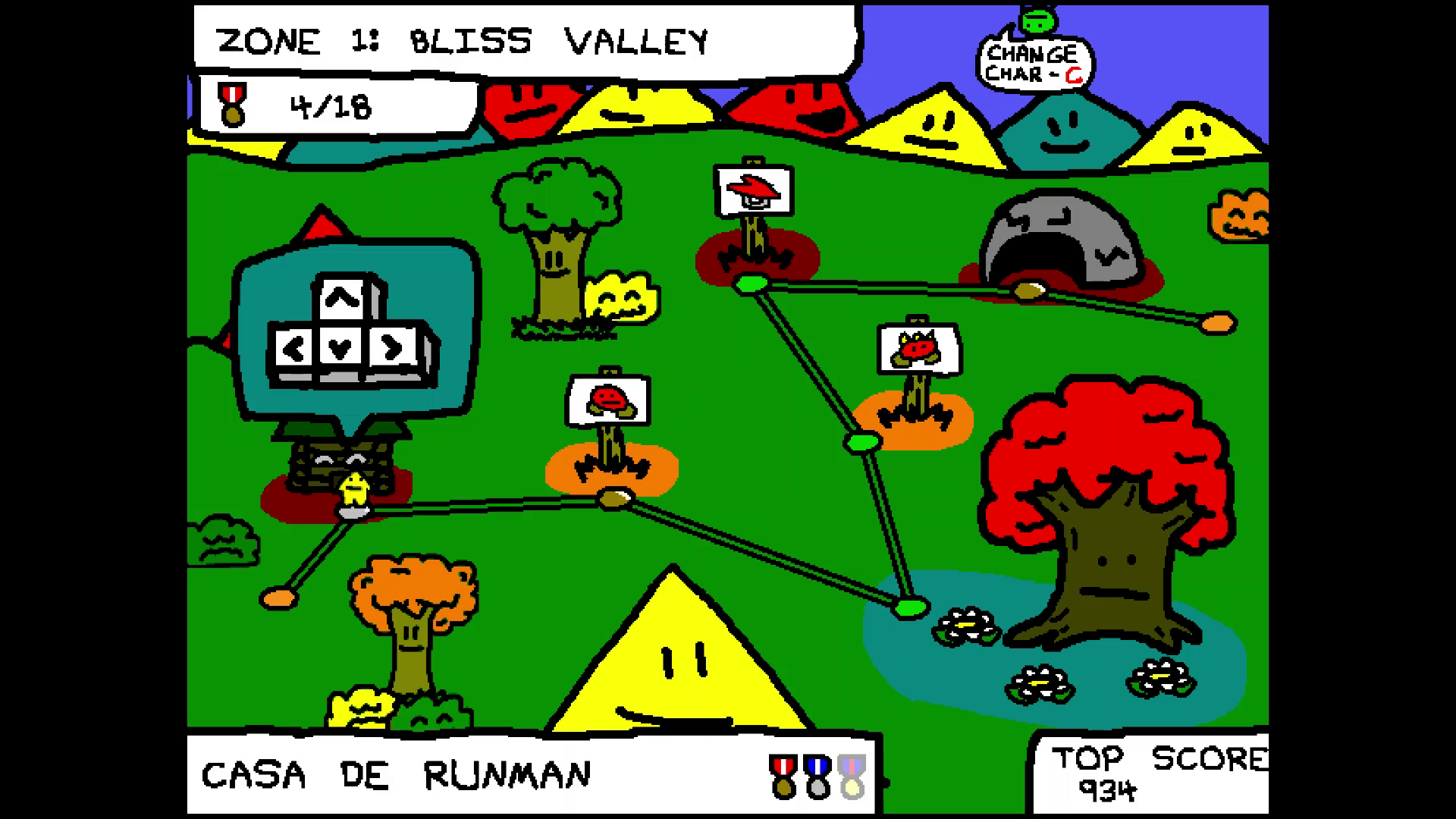

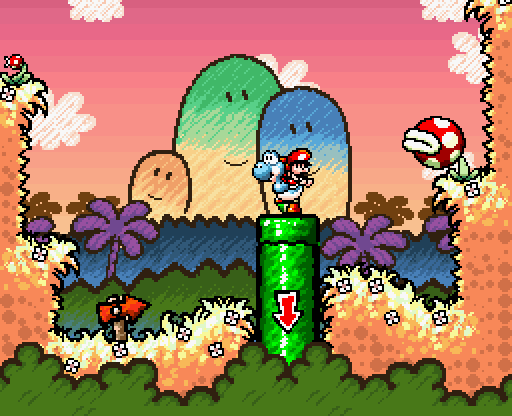

In RunMan: Race Around the World, each level is "about" something. There is a particular object, enemy, or terrain that appears early and often. This reinforces a sense of progression from level to level and world to world. Many great games do this. Maddy cited Super Mario World often. Level 1 is about the dinos. Level 2 is about the koopa troopers. Level 3 is about water. Etc.

It helps reinforce a core gaming and educational loop where you are shown a new problem, you learn how to solve it, then you repeat it with different variations on the problem that require you to synthesize new solutions. (This is "fun", basically)

That structure of repetition and progression was all Maddy. It helped click things into place. If I had been designing levels myself I would have just stuck whatever wherever. This often separates bad design from good, and good from great - creating with intention.

So Maddy gave us an amazing foundation for level design, and also technically. I was a reluctant programmer at the time and considered myself chiefly an artist and designer. Maddy took the reins coding our movement engine, which made it rock solid. At the time most people in the Game Maker community still struggled with, like, slopes. Our game had slopes, moving platforms, wallkicks, all this stuff that could be put together dynamically and work as expected.

Back then you didn't have the huge proliferation of Box2D and other pre-built physics systems, which are all built into game engines now and make it easy to put together stuff that just works. We did have a system something like that though, thanks to Maddy.

Maddy programmed our movement engine and did the bulk of the level design. I did all the art, characters, story, and soundtrack. Miscellaneous coding and general game design were shared, collaborative tasks.

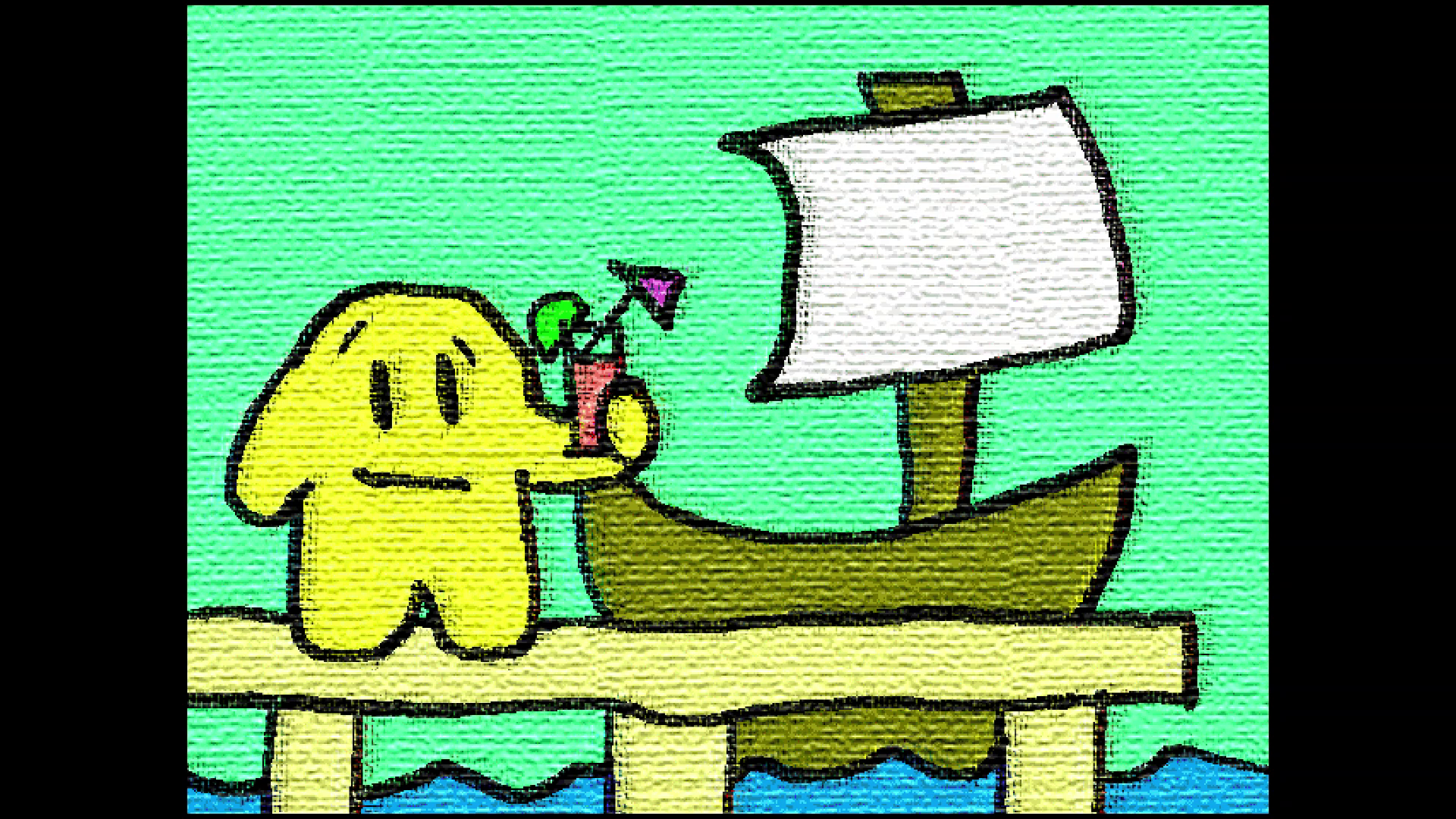

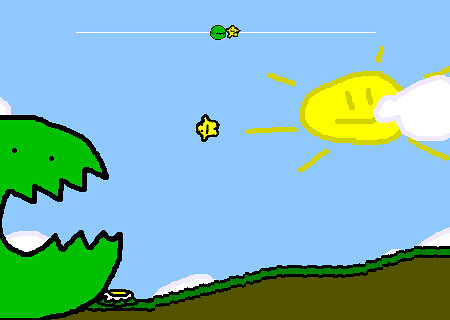

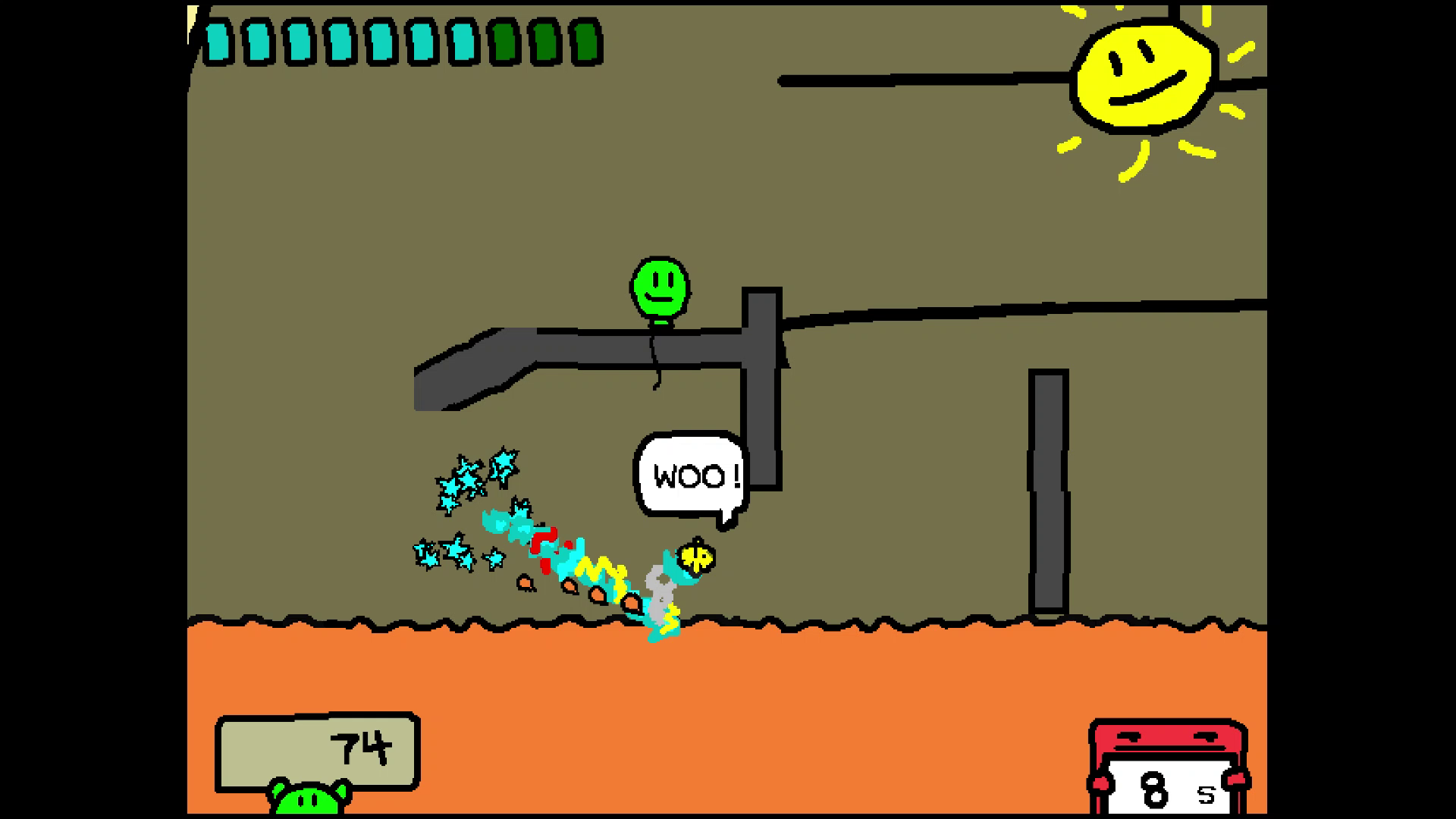

Visually, my goal with this game was just to deliver something that looked cohesive. I had been honing my art style but mostly winging it, and this was the first game I really tried to own it.

When I first started making games, I was literally drawing with a mouse in MS Paint. I had the old family computer (Windows 95) in my bedroom with the original Game Maker by Mark Overmars v3. The computer in the basement was the only one with an internet connection. So when I first uploaded the original RunMan, a small arcade game, I transferred it from my bedroom computer to the basement computer via floppy disk. Then I put it online.

By the time I was making RATW I used a tablet and Photoshop and wifi. Which is still pretty much my main workflow. I have used a Surface Pro now for many years. RATW and others were on a Wacom tablet and a homemade desktop tower with a crudely painted Penn State logo, the first and only PC I ever built.

So art wise I was really just trying to double down on what made my games look unique and charming, and make something I could produce myself reliably and efficiently, at generally low fidelity. Most monitors were not in HD when we started making this game. And my early tablets were small and not 1:1 with what I was drawing on-screen.

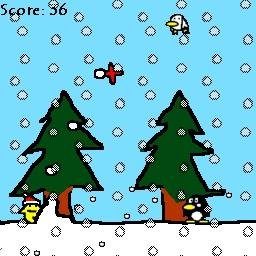

Thus I embraced some rules around how to draw and present everything. Generally, two different colors will never touch, without being separated by a line of black. Objects scale in+out instead of fading transparency. Everything gets a face.

I was still winging it on everything visually though. The game's color palette could be more refined, there are some incongruous character designs and effects. But overall it came together mostly how I envisioned it. People often compared it to Yoshi's Island, which was really flattering and to me interesting because that wasn't a game I was trying to emulate visually.

And if you look at the two, Yoshi's Island has a much more refined style, with more depth and texture. It's a gorgeous game. And it's also still very inline with the farily standard Mario style, though at the time seemed like quite a departure. And I think RATW evokes the same feelings in some players as YI, without looking like it exactly. It looks like the idea of YI's art style instead of looking like YI.

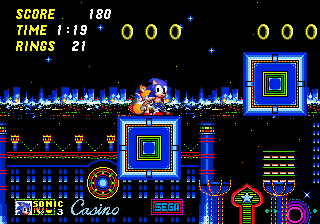

This was basically our approach to the gameplay, though with Sonic as the reference point. We wanted it to play like the idea of Sonic, instead of like Sonic. In your mind, the classic Sonic games (1-3, Knuckles, etc.) are fast and furious platformers with unrelenting momentum and flow. In reality, unless you're really really good, they are games full of traps and tricks and roadblocks that do everything they can to frustrate and slow you down.

So we wanted to make gameplay that was truly built around speed and flow, that played like an idealized performance of Sonic, regardless of skill level. My game design philosophy challenges a lot of the built-in "difficulty" bloat that gets added to games. Stuff like having a limited number of lives, or unfair checkpoint systems, respawning enemies, anything that makes the player repeat themselves or resets their progress. These things turn off less hardcore gamers and prevent people from actually playing/completing games, which to me is the whole point.

So I was really into the idea of making an easier version of Sonic, with a high skill ceiling for people to pursue if they wanted. And that was a good complement to Maddy's approach at the time, which was pretty much to make life hell for players. She helped invent masocore platforming. Which people loved! No one else was doing it! The genre went big-time with the release of Super Meat Boy. (Which of course featured both RunMan and Ogmo as playable characters.)

Our vision was that a perfect run in a level of RATW would look similar to Maddy's other games, requiring absolutely precise memory and timing with no margin for error. But unlike those games, if you messed up it wouldn't be insta-death.

The inspiration of Sonic gave us speed. The game's whole friendly vibe owes more to Nintendo. Super Mario World and Super Mario Bros. 3 were big inspirations, but I was also a N64 kid during some formative years, and a big fan of SM64, Banjo-Kazooie, DK64, etc.

In those games I always found myself revisiting "World 1", where there's green grass and blue skies and nonthreatening gameplay. It's fun to go back to those areas when you are skilled, as you have more freedom to mess around. I spent hours just running around doing flips off the mountain in Bob-bomb Battlefield.

And I thought, what if a whole game had that feel? Instead of increasing stakes and discomfort, with a claustrophobic water world or a doom-filled lava world, what if new areas were chill and friendly like world 1?

So that's what we went for. Maddy and I both hated the water levels in Sonic. And to a lesser extent Mario. They always change up your controls or stress you out about drowning. So in our water levels you just run right over/through it. In the lava levels, you just bounce off the lava.

The game is full of conscious tropes that we try to subvert. The water world and lava world being nonthreatening. Bottomless pits you can fall into ala Mario, that then hilariously spit you back out unharmed.

I think that's a consistent thread in my games, Maddy's games, and the games from our generation of game designers. We are the first wave of designers to grow up playing video games as we know them today. Our influences are very clearly other games, in a way that's not true for designers who came before us.

Likewise, the people now making games are growing into their craft in a world chock full of incredible indie games. Indie games have always been a thing - the earliest game developers were solo or on small teams, and there have always been artists doing boundary-pushing work at the margins. But when Maddy and I started making games, nobody called them "indie games", there were no storefronts for indie games, or any proven audience for indie games beyond the handful of other geeks making games in their basements.

Nowadays, as my good friend Salil once said, "indie games are just games". More people are making games than ever before, more amazing games are coming out than anyone can keep track of, and the lines between indie, AAA, and everything in between are more blurred than ever.

Making games has brought a lot of joy to my life. I have heard from players throughout my career who have been touched by my work, and I think that all makes us feel less alone in the world.

I hold a special place for those who have told me that my work inspired them to start making games. Particularly THIS game, which so intimidated me to start and to finish. THIS game was the one people played that made them say, "maybe I could do this", and to sit down and begin. THIS game helped inspire a generation of game designers who are out there at the forefront of the most important artform of our time. Pretty groovy.

RunMan: Race Around the World launches on Steam for the first time this Tuesday, October 1st.